History of Sunderland A.F.C.

Sunderland Association Football Club are an English association football club based in Sunderland, Tyne and Wear. They were formed in 1879, and played several years in the FA Cup and local cup competitions before joining the Football League in the 1890–91 season in place of Stoke. They played in the top league in England until the 1957–58, season when they were relegated into the Second Division. Sunderland are England's sixth most successful club of all time,[1] having won the English League championship six times: in 1892, 1893, 1895, 1902, 1913, and, most recently, in 1936. They have also been runners-up on a further five occasions: in 1894, 1898, 1901, 1923 and 1935 (see Sunderland A.F.C. seasons).

Sunderland have also won the FA Cup twice, in 1937 against Preston North End and in 1973 against Leeds United. They were finalists in 1913 and 1992, where they were beaten respectively by Aston Villa and Liverpool. They were finalists in the 1985 and 2014 Football League Cup Final, where they were beaten respectively by Norwich City and Manchester City. Their other honours include two Charity Shields, in 1902 and 1935.

Early years and "The Team of all Talents": 1879–1913

[edit]Sunderland AFC began life as "Sunderland & District Teachers Association Football Club", and was announced to the world on 27 September 1880 by The Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette.[2] Originally organised in 1879 by James Allan, a teacher at Hendon Board School,[3][4] with the objective to provide "recreational amusement" for the area's schoolteachers.[3] Their first recorded competitive game was against Ferryhill Athletic on 13 November 1880, which they lost 1–0. Their first kit was an all blue strip, a contrast to the red and white stripes they play in currently.[5] Their first ground was the Blue House Field in Hendon, close to James Allan's school, and they would change their home four times in seven years before settling at Newcastle Road in 1886.[6]

On 16 October 1880 the Sunderland Daily Echo and Shipping Gazette announced that the club's name had been changed to Sunderland Association Football Club; and non-teachers were allowed to join.[7] They turned professional in 1885, the same year that the club recruited a number of Scotsmen, their first internationally capped players.[8] Founder James Allan left Sunderland in 1888 because of his dislike for the "professionalism" that had been creeping into the club, and subsequently formed Sunderland Albion.[9] Tom Watson became Sunderland's first manager when he was appointed in 1888.[10] On 5 April 1890, the Football League's founder, William McGregor, labelled Sunderland as "the team of all talents" stating that they had "a talented man in every position".[11]

Sunderland's games consisted of local competitions and the FA Cup. Additionally, they participated in friendlies with Football League clubs; they beat the League champions Preston North End on 28 April 1889.[12] As their popularity grew, they applied for admission into the Football League. At the League's annual meeting that considered this application, Sunderland offered to pay towards other clubs' travelling costs, to compensate for the extra distance these club would need to travel. This offer secured their place in the Football League.[11] They replaced Stoke, one of the original League founding members, who failed to be re-elected.[13] In their second season in the Football League, Sunderland won the title, by five points over Preston North End.[14] This success was repeated in the following season, when Sunderland won their second League title, this time 11 points ahead of their nearest contenders.[15] That season also included an 8–1 win over West Bromwich Albion.[15]

They came close to winning three successive League championships in the 1893–94 season, when they finished as runners-up to Aston Villa.[16] The club shared this period of success with Aston Villa; the battles between these clubs were the subject of a Thomas Hemy painting of the two clubs during the 1894–95 season This is one of the earliest recorded paintings of a competitive Football League match; entitled A Corner Kick, the painting now stands in the doorway of Sunderland's current stadium, the Stadium of Light.[17] Sunderland achieved their third League title in four seasons in the 1894–95 season,[16] and after their League championship success took part in a game with Heart of Midlothian, the champions of Scotland. The game was played on 27 April 1895, and was described as the "Championship of the World title match". Sunderland won the game 5–3 and were crowned "Champions of the World".[16][18]

The wealthy miner Samuel Tyzack, who alongside and shipbuilder Robert Turnbull funded the "team of all talents," often pretended to be a priest while scouting for players in Scotland, as Sunderland's recruitment policy enraged many Scottish fans. In fact, the Sunderland lineup in the 1895 World Championship consisted entirely of Scottish players[19][18] (English-born Tom Porteous and Irish-born David Hannah were also involved in the period, but both were raised in Scotland and recruited from local clubs there).

Together with Aston Villa, Sunderland were the subject of one of the earliest football paintings in the world – possibly the earliest – when in 1895 the artist Thomas M. M. Hemy painted a picture of a game between the teams at Sunderland's then ground Newcastle Road.[20]

In their first three league titles, Johnny Campbell was the top scorer of the league.[21] Also notable in the attack at the time, and important to Campbell's success in attack, were other "Team of all Talents" players Jimmy Hannah and Jimmy Millar.[22][23] As goalkeeper, Ned Doig set a 19th-century world record by not conceding any goals in 87 of his 290 top division appearances (30%).[24]

Further titles and the move to Roker Park: 1896–1913

[edit]

After taking Sunderland to three English League championship titles manager Watson resigned at the end of the 1895–96 season, in order to join Liverpool.[25] Robert Campbell replaced him.[25] From 1886 until 1898, Sunderland's home ground was in Newcastle Road.[26] In 1898, the club moved to what would become their home for almost a century, Roker Park.[27] Initially the ground had a capacity of 30,000.[27] However, over the following decades it was continually expanded, and at its peak would hold an official crowd of over 75,000 in a sixth round FA Cup replay against Derby County on 8 March 1933.[28] Campbell did not achieve the same playing success as former manager Watson, as Sunderland failed to win any titles in his three seasons at the club, which he left in the 1898–99 season to join Bristol City.[29] Scotsman Alex Mackie replaced Campbell as manager, and gained success in the 1901–02 season when Sunderland won their fourth League title.[30] He followed this up with victory in the Sheriff of London Charity Shield, a competition featuring the best amateur and professional sides in England. Sunderland beat leading amateurs Corinthians 3–0.[31]

In December 1902, Sunderland joined Arthur Bridgett. He went on to captain the "Black Cats" for ten years and gain his eleven England caps, making him Sunderland's second most-capped England International behind Dave Watson.[32]

In 1904 Sunderland were involved in a financial irregularity, when the club's board of directors gave their right back Andy McCombie £100 (£13,600 today) to start a business, with the view that his benefit game would enable him repay the money.[33][34] McCombie however, saw the money as a gift and refused to pay back the club. The Football Association launched an inquiry and agreed with McCombie, stating that it was a "resigning/win/draw bonus". The club's records showed further breaches of the League's financial rules.[33] As a result, Sunderland were fined £250 (£34,000 today)and six directors were suspended for two and a half years.[33][34] McCombie later signed for Newcastle United, and helped towards their spell of League success.[33]

After 214 matches in charge of Sunderland, Mackie left the club as a result of the "McCombie affair".[35] He was replaced by Irishman Bob Kyle; another 70 candidates had also applied for the managerial.[36] In 1905 Sunderland were involved in the first £1,000 (£135,600 today) transfer fee for a player, when Alf Common signed for Middlesbrough.[34][35] The 1907–08 season included Sunderland's record League win, a 9–1 victory against Newcastle United at St James' Park.[37] Billy Hogg and George Holley each scored hat-tricks, while Arthur Bridgett scored two.[38]

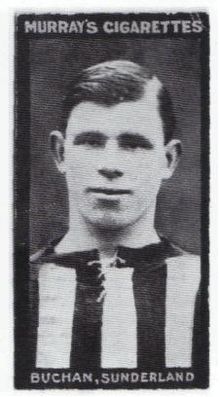

Kyle achieved his only League championship in charge of Sunderland in the 1912–13 season, when they won the League with 54 points.[39] On 19 April 1913 Sunderland narrowly missed out on becoming one of the few clubs to win the League and cup double, when they were beaten 1–0 by Aston Villa in the FA Cup Final at Crystal Palace.[40] This period in their history also saw the goalscoring of Charlie Buchan, who went on to score 221 goals for Sunderland,[41] making him (as of 2009) the second highest goal-scorer in the club's history, behind Bob Gurney.[42] Other prominent players of that period's Sunderland was George Holley, who was league top scorer in the season before the title, and Scottish Charles Thomson who captained the club.

First World War and inter-war period, 1913–1939

[edit]Sunderland finished in eighth place in 1914–15 Division One season,[43] before World War I forced the break-up of the team as men went off to fight on the continent.[44] Charlie Buchan and Bob Young each went on to win the Military Medal.[44] After the resumption of the Football League following the war, Sunderland finished fifth in the 1919–20 season.[45]

To consolidate themselves in the First Division, Sunderland made several large money signings, including a world record fee of £5,500 (£379,000 today) for the signing of Warney Cresswell from South Shields.[34][46] In the 1922–23 season they came close to another League championship title, finishing runners-up to Liverpool by six points with Buchan breaking the 30 goal mark.[47] In the 1923–24 season Sunderland were involved in a dispute with the English and Scottish national teams. Buchan and William Clunas had been called up by England and Scotland respectively. Sunderland were two points clear at the top of the table, but without Buchan and Clunas they travelled to Arsenal and were beaten 2–0, a defeat which helped cost them the title race for that season.[48]

In April 1925, Sunderland completed the signing of centre forward Dave Halliday, after Buchan left for Arsenal.[49] In his second season Halliday scored 38 goals, helping Sunderland secure a third-place finish in the League.[50] In the 1928–29 season Halliday scored 43 goals, a club record for the most individual goals in a season.[51] Kyle, who had been Sunderland's manager since 1905, resigned at the end of the 1928–29 season, after 25 seasons in charge of the club, managing 817 matches and taking Sunderland to the verge of a League and cup double.[52] He was replaced by Johnny Cochrane, who arrived from St Mirren.[51] With Cochrane in charge, Sunderland reached the 1930–31 FA Cup semi-final, where they lost to Birmingham City.[53] Sunderland's next success came in the 1934–35 season when they finished as runners-up to Arsenal.[54] The following season Sunderland managed to win their sixth League title, by a margin of eight points. They scored 109 goals during the season, with Raich Carter and Bobby Gurney each scoring 31.[55]

Despite winning the league, the seasons did not go without tragedy. The young goalkeeper of the team, Jimmy Thorpe, died as a result of a kick in the head and chest after he had picked up the ball following a backpass in a game against Chelsea at Roker Park. He continued to take part until the match finished, but collapsed at home afterwards and died in hospital four days later from diabetes mellitus and heart failure 'accelerated by the rough usage of the opposing team.'[56] The tragic end to Thorpe's career led to a change in the rules, where players were no longer allowed to raise their foot to a goalkeeper when he had control of the ball in his arms.[57]

The League championship led to Sunderland playing in the Charity Shield against FA Cup-winners Arsenal. Sunderland won the shield after goals from Eddie Burbanks and Raich Carter.[58] Their success continued in the 1936–37 season, when they achieved their first FA Cup win. They beat Preston North End 3–1 in the final as Bobby Gurney, Raich Carter, and Eddie Burbanks all scored goals at Wembley Stadium.[59] Sunderland competed in the Charity Shield for a second successive season, this time against Manchester City who had won the League title in 1936–37; Sunderland were beaten 2–0.[58] Their FA Cup success looked set to continue in the 1937–38 season, when they reached the semi-finals, but they were beaten 3–1 by Huddersfield Town, to end their chances.[60] Cochrane announced his retirement from management in 1939, after he had been in charge of Sunderland for 11 seasons, taking them to a League title, and an FA Cup win.[61]

Second World War and postwar period, 1939–1959

[edit]

Bill Murray was appointed Sunderland's manager in 1939.[62] On the outbreak of war the League competition was suspended shortly after the start of the 1939–40 season, halting the new manager's progress.[63] The FA Cup was also suspended, but a replacement tournament, the Football League War Cup, was introduced.[64][better source needed] Sunderland took part in the two-legged War Cup final in the 1941–42 season, against Wolverhampton Wanderers.[65] The first leg was drawn 2–2 at Roker Park, but Wolves won the return leg at Molineux 4–1 to win the trophy.[65] During the war Roker Park suffered damage from bombs which destroyed the Roker End clubhouse; a police constable was killed while patrolling the stadium's perimeter.[66] In the 1945–46 season, after the end of the war while the League was still suspended, the FA Cup resumed. Sunderland reached the fifth round where they were beaten by Birmingham City.[67] The League resumed the following season, Sunderland finishing in ninth place.[68] In the 1947–48 season the club finished in twentieth place, on the brink of being relegated from the League's Division one for the first time.[69]

In January 1949, Sunderland were involved in what is often regarded as the first case of a player transferring himself when they paid £18,000 (£803,000 today) for Carlisle United player-manager Ivor Broadis, who handled transfer negotiations himself.[34][70] In the 1948–49 season, Sunderland visited Yeovil Town in the fourth round of the FA Cup. Yeovil were a non-League club at the time, but beat Division One side Sunderland 2–1 to knock them out of the Cup.[71] However, Sunderland's next season was more successful; they finished third in the League, and were its top scorers with 83 goals.[72] They also had the League's top goalscorer, Dickie Davis with 25 goals.[73] In the 1950–51 season, Sunderland paid a world record transfer fee when signing Welsh striker Trevor Ford from Aston Villa, for £30,000 (£1,300,000 today), during a time when Sunderland were known as the "Bank of England club" because of their large money signings.[34][74]

For Sunderland, the immediate post-war years were characterised by significant spending; the club paid £18,000 (£803,000 today) for Carlisle United's Ivor Broadis in January 1949.[34] Broadis was also Carlisle's manager at the time, and this is the first instance of a player transferring himself to another club.[75] This, along with record-breaking transfer fees to secure the services of Len Shackleton and Welsh international Trevor Ford, led to a contemporary nickname, the "Bank of England club".[76] The club finished third in the First Division in 1950,[77] their highest finish since the 1936 championship.

Len Shackleton, known as the "Clown Prince of Soccer", later admitted that the players were more a collection of talented individuals than a true team, and that "it takes time to harness and control a team of thoroughbreds. It took time to achieve the blend at Roker Park".[78] Shackleton and centre-forward Trevor Ford would never build any kind of relationship on or off the pitch however, and Ford once threatened to never play in the same Sunderland team as Shackleton until he was forced to back down by manager Bill Murray.[79] Ford was sold on to Cardiff City in November 1953.[80]

In January 1957, a letter was delivered to The Football Association (FA) from "Mr Smith", in which the author made allegations that Sunderland were making illegal payments to players.[81] The FA sent an investigation team, which found evidence of illegal payments in the Sunderland accounts, including a £3,000 (£91,000 today) bill, supposedly for straw to cover the pitch.[34][81] The investigators uncovered a string of similar accounting glitches; contract companies were purposely charging Sunderland excessive fees for services, and later sending credit-notes to redress the balance. These credit notes were passed on to players.[81] In total, just over £5,000 (£152,000 today) was handled in this way.[34][81] The club's chairman and chief financial officer, along with three other club directors, were permanently suspended. Sunderland were fined £5,000 (£152,000 today), manager Murray was fined £200 (£6,100 today), and a number of players, including record-signing Trevor Ford were temporarily suspended€ from the game.[34][81] In the aftermath of the event, manager Bill Murray was replaced by Alan Brown.

In 1958, with Brown in charge, Sunderland were relegated from Division One for the first time in their history,[82] bringing their 68-year stay in England's top division to an end. Going into the final game of the season, they still had a chance of avoiding relegation, if they could win their game against Portsmouth and if Leicester City could be held by Birmingham City.[82] Sunderland won their game 2–0,[83] but Birmingham could not prevent Leicester from winning, thus Sunderland were relegated.[82]

FA Cup glory and Europe: 1959–1979

[edit]After Sunderland's first relegation from Division One in the 1957–58 season, the club at first languished in the lower half of Division Two, finishing the 1959–60 season in sixteenth place.[84] Two finishes in third place followed in the 1961–62 and 1962–63 seasons, Sunderland in each case missing out on promotion by just one position. The 1961–62 season also saw the retirement of Brian Clough due to injury,[85] after he had scored 63 goals in 74 games for the club.[86] After six years in Division Two, Sunderland were promoted back to the First Division at the end of the 1963–64 season.[87]

In 1964 Brown left his managerial post at Sunderland on appointment as manager of Sheffield Wednesday. After Sunderland had played through three months of the 1964–65 season without a manager, George Hardwick took over on a caretaker basis,[88] until Ian McColl was appointed on a permanent basis at the end of the season.[89] Brown returned for a second spell at Sunderland in 1968.[90] After their promotion Sunderland failed to make an impact in Division One, never finishing higher than fifteenth in six years, after which they were relegated for the second time.[91] Billy Elliott, a former Sunderland player, took over after Brown's second departure,[92] but managed the team for only four matches before former Newcastle United player Bob Stokoe was appointed as permanent manager.[92]

An intriguing interlude came about in 1967, when Sunderland spent a summer in North America playing in the United Soccer Association, a league which imported various international clubs. Sunderland worked in North America under the name Vancouver Royal Canadians, finishing fifth in the league's Western Division.

In 1973, as a Second Division side, Sunderland reached the FA Cup Final, where they beat the cup-holders Leeds United. A first half goal by Scotsman Ian Porterfield was the only goal of the game. Jimmy Montgomery produced a double save, first from a Trevor Cherry header, and then from a shot by Peter Lorimer, to prevent Leeds from scoring.[93] At the end of the game Sunderland manager Stokoe ran onto the pitch to embrace his goalkeeper, a gesture perpetuated by the statue currently standing outside the Stadium of Light.[94] Only two other clubs, Southampton in 1976,[95] and West Ham United in 1980,[96] have since equalled Sunderland's achievement of lifting the FA Cup while playing outside the top tier of English football.[96] In 1973, Bobby Knoxall recorded "Sunderland All The Way" for the 1973 FA Cup Final record.[97]

The FA Cup win in 1973 meant that Sunderland, for the first time in their history, had qualified for a European competition, in this case the UEFA Cup Winners' Cup.[98] They were first drawn against Hungarian side Vasas Budapest, who they beat 3–0 on aggregate.[98] In the next round Sunderland were drawn against Sporting Lisbon. They won the first leg 2–1 at Roker Park, but in the return leg in Lisbon they were beaten 2–0, and were thus knocked out of the competition in the second round.

In 1976 Sunderland were again promoted to the First Division, as Division Two champions.[99] Stokoe became ill during the 1976–77 season; he stepped down from the job, and was replaced temporarily by caretaker manager Ian MacFarlane. McFarlane's stay was short, and he was replaced by Jimmy Adamson in 1976. After promotion in the previous season, Sunderland were relegated back to the Second Division.[100] Adamson managed them for just two seasons before resigning to move to Leeds United.[101] In a flurry of many managers in a short time period, David Merrington took over as caretaker manager.[101] Billy Elliot then joined Sunderland as manager for a second time, replacing Merrington until the end of the season.[101]

Two cup finals: 1979–1997

[edit]Sunderland celebrated their centenary in the 1979–80 season with a testimonial match. They played an "England XI", featuring players from Newcastle United and from Middlesbrough; they lost the game 2–0.[102] In 1979, after Elliot ended his spell, Ken Knighton took the vacant manager's position.[102] Knighton managed Sunderland for 94 games, leading them in his first season to second place in Division Two, and promotion to the First Division,[103] However, he was sacked the following season, when Sunderland were struggling near the bottom of Division One.[104] Mick Docherty was brought in as caretaker manager until the end of the 1980–81 season, and helped them avoid relegation.[105]

The activity in the Sunderland manager's seat continued, with Alan Durban's appointment in 1981.[106] He lasted two years, before being sacked in the 1983–84 season after a defeat by Manchester United. Former player Pop Robson was brought in for a single game,[107] before Len Ashurst's appointment as regular manager. In the 1984–85 season Ashurst led Sunderland to their first League Cup final, where they lost 1–0 to Norwich through an own goal from Gordon Chisholm, after Clive Walker had missed a penalty for Sunderland.[108] At the end of the season Sunderland were relegated back to the Second Division,[109] and Ashurst was sacked.[110]

Lawrie McMenemy was brought in as manager in 1985,[110] but Sunderland reached the lowest point in their history in 1987, when they suffered relegation to the Third Division after losing a two-leg play-off to Gillingham.[111] The return of 1973 FA Cup winning manager Bob Stokoe,[112] appointed caretaker manager following the sacking of McMenemy, could not help Sunderland avoid relegation. It was the first time in their history that they had fallen into the Third Division. However, under new manager Denis Smith, promotion was gained at the first attempt; Sunderland returned to the Second Division as Third Division champions in 1988.[113]

Two years later, Sunderland reached the Second Division play-off final, after beating Newcastle United in the semi-final. During the second leg of the semi-final at St. James' Park, some Newcastle fans, seeing their team down 2–0 with only five minutes remaining, invaded the pitch in the hope of forcing an abandonment.[114] However, the game was resumed and Sunderland completed the win.[115] In the play-off final, Sunderland lost 1–0 against Swindon Town at Wembley. However Sunderland were promoted a few weeks later in place of Swindon, who were kept in the Second Division after admitting financial irregularities.[116]

After just one season in the First Division, Sunderland were relegated again.[117] They subsequently struggled in Division Two, in 1991–92. However, in that season Sunderland embarked on a run leading to the FA Cup final, where they lost 2–0 to Liverpool,[118] They had previously beaten Chelsea in a quarter-final replay.[119] Smith had quit as manager during the season, and was replaced by his assistant Malcolm Crosby.[120] He in turn resigned after less than a year, and was replaced by the ex-England player Terry Butcher.[121]

Before the end of 1993, Butcher's reign as manager came to an end after 45 games in charge, and he was replaced by Mick Buxton.[122] In a period which included six managers in ten years, Buxton was sacked in 1995.[123] Sunderland's board turned to Peter Reid as temporary manager, in the hopes of keeping Sunderland clear of relegation.[124] That objective was achieved within weeks, and Reid was rewarded with a permanent contract.[124] Reid's first full season as Sunderland manager, 1995–96, was successful; the club won the Division One title and gained promotion to the Premier League for the first time since the League restructuring which had taken effect in 1992–93.[125] In the 1996–97 season, despite beating Manchester United,[126] Arsenal[127] and Chelsea[128] they were relegated.[129]

In 1998, BBC broadcast a six-part documentary named Premier Passions. It chronicled Sunderland A.F.C. during the 1996–97 season, in which the club was relegated from the Premier League, the year after winning promotion from the Football League First Division, and the move to Stadium of Light.[130][131]

New stadium: 1997–2008

[edit]In the 1996–97 season Sunderland relocated to the 42,000-seat Stadium of Light at Monkwearmouth, after 99 years at Roker Park.[132] Fans reaction was mixed, and following the demolition of Roker Park, playwright Tom Kelly and actor Paul Dunn created a one-man play called "I Left My Heart at Roker Park" about a fan struggling with the move and what Roker Park meant for him – the play originally ran in 1997, and had a few revivals since.[133][134][135][136]

Actor and Sunderland supporter Peter O'Toole, described Roker Park as his last connection to the club and that everything "they meant to him was when they were at Roker Park" and that as a result he wasn't as much a fan as he used to be.[137][138][139]

The stadium's capacity was later expanded to 49,000 seats, making it the fourth largest club stadium in England.[132] In recognition of the historical importance of the mining industry in the club's main area of support, a Davy Lamp currently stands outside the stadium.[140]

In their first full season at the new ground, 1997–98, Sunderland finished third in Division One.[141] After beating Sheffield United in the Football League play-offs semi-final,[111] they reached the final at Wembley with a place in the Premier League at stake. Over 40,000 fans travelled from the North-East to see the game against Charlton Athletic. The match was drawn 4–4 after extra time had been played; Charlton, however, won the game on a penalty shootout, after Michael Gray had his penalty saved by Charlton goalkeeper Saša Ilić.[142]

In the 1998–99 season Sunderland secured their Premier League place by winning the Division One title with a then record 105 League points.[143] They clinched promotion at Bury by winning 5–2.[144] Kevin Phillips won the European Golden Shoe in his first top-flight season with Sunderland, scoring 30 goals.[145]

In September 2001, Sunderland chairman Bob Murray announced the separation of Sunderland's charitable and community work from the mainstream club activity, and the independent SAFC Foundation was created.[146] Later, the foundation came to be known as the Foundation of Light.

In 2001–02 Sunderland narrowly avoided relegation. They were the lowest scoring team in the Premier League,[147] with 29 goals, ending the season in seventeenth place and being knocked out of both English Cup competitions in their first rounds.[147] In 2002–03 they finished at bottom of the Premier League, with 4 wins, 21 goals, and 19 points, an English Premiership record low at that time.[148] Reid had been sacked as manager in October and been replaced by Howard Wilkinson, with Steve Cotterill as his assistant.[149] Wilkinson's reign was unsuccessful, and he left the club after only six months in charge.[150] Former Republic of Ireland manager Mick McCarthy came to the club in March 2003, but could not prevent relegation.[151]

In the 2003–04 season Sunderland finished third in Division One,[152] and only a penalty shoot-out defeat at the hands of Crystal Palace prevented them from reaching the play-off final for a promotion place.[153] In the 2004–05 season, Sunderland finished at the top of the table in Division One, now rechristened the Football League Championship, and thus returned to the Premier League.[154] The 2005–06 season was poor for Sunderland, as they failed to win a home game before Christmas and were eventually relegated with a new record lowest points tally of 15, breaking their own previous record of 19.[155] McCarthy was sacked in March and replaced by caretaker manager Kevin Ball.[156] He took Sunderland to their first home win of the season, a 2–1 victory over Fulham.[157]

On 6 August 2007, Sunderland celebrated 10 years at the Stadium of Light with a draw against Juventus,[158] and prepared for the oncoming season by spending nearly £40 million on new players for the squad,[159] whilst also breaking the British transfer record for a goalkeeper with the £9 million transfer of Craig Gordon.[160] Sunderland secured their Premier League status for the 2008–09 season after a derby victory over Middlesbrough, and with teams below failing to win.[161] On 25 October 2008, Sunderland defeated rivals Newcastle United 2–1 at the Stadium of Light, their first home win over them since 1980, and the first time they had ever defeated them at that ground.[162] on 4 December 2008, Keane left Sunderland after a run of defeats in the Premier League.[163] First-team coach Ricky Sbragia took over as caretaker manager,[163] and on 27 December 2008 Sbragia took the job on a permanent basis, signing an 18-month contract.[164] Despite promising early results, the team continued to struggle and narrowly avoided relegation from the Premiership on the last day of the season, after which Sbragia resigned from his post.

2008–present

[edit]Irish-American tycoon Ellis Short completed a full takeover of the club from the Irish Drumaville Consortium,[165] and Steve Bruce was announced as the new manager on 3 June 2008.[166]

After being named Sunderland's Young Player of the Year for two consecutive seasons,[167] at the end of the 2010–11 season, Jordan Henderson was transferred to Liverpool F.C., where he went on to become captain and win the Champions League.[168][169]

Despite signing numerous new players before the 2012–13 season, Sunderland endured a difficult start to the season, with their first victory not coming until late September against Wigan. Despite the £5 million signing of Danny Graham in January, Sunderland suffered a further slump, taking just 3 points from eight games, and with the threat of relegation looming, manager Martin O'Neill was sacked on 30 March, following a 1–0 home defeat by Manchester United.[170] Paolo Di Canio was announced has his replacement the following day,[171] bringing his own backroom staff. The appointment prompted the immediate resignation of club Vice Chairman David Miliband due to Di Canio's "past political statements".[172] The appointment of Di Canio also sparked opposition from the Durham Miners' Association,[173] which threatened to remove one of its mining banners from Sunderland's Stadium of Light, which is built on the former site of the Wearmouth Colliery, as a symbol of its anger over the appointment.[174][175] The background to the opposition was past statements made by Di Canio supporting Fascism.[173][176]

In his first season, Paolo Di Canio succeeded in keeping Sunderland in the Premier League,[177][178] but the 2013–14 season proved to be less of a success, and Di Canio was sacked after picking up just one point in five league games. On 8 October 2013 when Gus Poyet was appointed manager of Sunderland.[179]

Poyet took over at Sunderland during the 2013-14 Premier League campaign.[180] Although he had a rough start to his tenure as Sunderland manager, suffering a 4–0 defeat to Swansea in his first match in charge,[181] Poyet ended up securing Premier League safety in the penultimate game of the season.[182] He also took Sunderland to the League Cup Final in the same season, defeating Manchester United in penalty kicks in the semi-finals. These achievements earned Poyet a new two-year contract with the club on 28 May 2014.[183]

The following season was less of a success for Gus Poyet, with Sunderland just above the bottom three after a 4–0 defeat to Aston Villa on 14 March 2015.[184] Two days after the defeat, the club sacked Poyet due to the bad run of results that left Sunderland in 17th, just one point above the relegation zone.[185] Sam Allardyce replaced Poyet and guided them to a 17th-place finish with a 3 - 0 home win over Everton, thus dumping Newcastle into the Championship.

Sam Allardyce took the position of England manager and was replaced by David Moyes.

Sunderland finished the 2016–17 season 20th in the Premier League and were relegated to the Championship under David Moyes, In June 2017, goalkeeper Jordan Pickford, a product of Sunderland's academy who joined the club aged eight, was transferred to Everton for a fee of £25 million, rising to a possible £30 million, a record for a British goalkeeper.[186]

Sunderland finished the 2017–18 season 24th in the Championship and found themselves in EFL League One, a second consecutive relegation. The events of the season formed the backdrop to the documentary series Sunderland 'Til I Die which was released on Netflix on 14 December 2018.[187] Sunderland finished their season having had four managers. David Moyes, who had overseen the previous seasons relegation, resigned and was replaced by Simon Grayson. He was subsequently replaced by Chris Coleman. Due to the success of the first season, a second season of Sunderland 'Til I Die was confirmed by Netflix, despite many in the club opposing it.[188][189]

In April 2018, the team was purchased by a consortium led by Stewart Donald, with Ellis Short selling it after a second successive relegation to League One.[190] Steward Donald agreed to sell Eastleigh so that he could own Sunderland.[191] On 21 May, he officially became owner of Sunderland, doing so without the consortium to speed the transition.[192]

St Mirren manager Jack Ross was appointed as manager in May 2018 to take charge of what is only the club's second-ever season in the third flight of the English football league system.[193] In their first season in League One, the team finished 5th and reached the playoff final, but lost to Charlton Athletic at Wembley.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- General

- Paul Days; John Hudson; John Hudson; Bernard Callaghan (1 December 1999). Sunderland AFC: The Official History 1879–2000. Business Education Publishers Ltd. p. 336. ISBN 978-0-9536984-1-7. ASIN 0953698416.

- Garth Dykes; Doug Lamming (November 2000). All the lads: A complete who's who of Sunderland A.F.C. Polar Print Group Ltd. p. 312. ISBN 978-1-899538-14-0. ASIN 1899538143.

- Malam, Colin (2004). Clown Prince of Soccer? The Len Shackleton Story. Highdown. ISBN 1-904317-74X.

- "Sunderland AFC — Statistics, History and Records". The Stat Cat. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- "Sunderland AFC honours". Ready To Go : Independent Sunderland AFC. Archived from the original on 18 September 2008. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- Specific

- ^ "England – List of Champions". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 1 March 2009.

- ^ "Happy Birthday Sunderland AFC – 136 Years Old! – Ryehill Football". ryehillfootball.co.uk.

- ^ a b Days, pp. 3–4.

- ^ John Simkin BA. MA, MPhil. "Spartacus Educational James Allan". Spartacus Schoolnet. Archived from the original on 9 December 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ Days, p. 15.

- ^ Days, p. 3.

- ^ Days, p. 7.

- ^ Days, p. 13.

- ^ Days, p. 18.

- ^ "Past Managers 1889–1939". Sunderland A.F.C. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ a b Days, p21.

- ^ Days, p20.

- ^ Days, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Days, pp. 29–30.

- ^ a b Days, pp. 31–32.

- ^ a b c Days, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Days, p. 38.

- ^ a b When Sunderland met Hearts in the first ever 'Champions League' match, Alexis James, Nutmeg Magazine, September 2017

- ^ Sunderland's Victorian all-stars blazed trail for money's rule of football, Jonathan Wilson, The Guardian, 25 April 2020

- ^ "The famous Sunderland v Aston Villa painting that hangs in the lobby of the SoL – a history of". 21 November 2017.

- ^ "Sunderland's First Great Centre Forward". 20 July 2016.

- ^ "Johnny Campbell – Ryehill Football".

- ^ "The Scotch Professors and 'combination football'". 18 March 2018.

- ^ "HISTORY : CURIOSITIES OF WORLD FOOTBALL (1891-1900) | IFFHS". Archived from the original on 27 August 2019.

- ^ a b Days, p. 39.

- ^ Days, p. 44.

- ^ a b Days, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Days, p. 134.

- ^ Days, p. 45.

- ^ Days, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Days, pp. 59–60.

- ^ "A Love Supreme". Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ^ a b c d Days, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ a b Days, p. 65.

- ^ Days, p. 68.

- ^ Days, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Days, pp 73–76.

- ^ Days, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Days, pp. 87–90.

- ^ Dykes, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Dykes, pp. 170–171.

- ^ Richard Rundle. "Football League 1914–15". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ a b Days, p. 95.

- ^ Richard Rundle. "Football League 1919–20". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 27 December 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Days, p. 106.

- ^ Days, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Days, p. 109.

- ^ Days, p. 114.

- ^ Days, pp. 117–118.

- ^ a b Days, p. 124.

- ^ Days, p. 121.

- ^ Days, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Days, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Days, pp. 139–142.

- ^ "Goalkeeper's Death". The Times. London. 14 February 1936.[dead link]

- ^ "On the run with dogs and a long-dead goalkeeper – Telegraph". London. Archived from the original on 11 March 2007.

- ^ a b "England — List of FA Charity/Community Shield Matches". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ Days, pp. 143–146.

- ^ Days, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Days, p. 149.

- ^ Days, p. 150.

- ^ Richard Rundle. "Football League 1939–40". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Football League War Cup". Spartacus Educational. Archived from the original on 8 July 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- ^ a b "1942 War Cup Final". Roker Roar. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ Days, p. 153.

- ^ "English FA Cup 1945/1946". Soccerbase. Archived from the original on 25 May 2005. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Days, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Days, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Mike Arnos (14 December 2007). "Broadis still; bubbling along at 85". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Days, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Days, pp. 163–164.

- ^ "Football League Div 1 & 2 Leading Goalscorers 1947–92". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ Days, p. 169.

- ^ Amos, Mike (14 December 2007). "Broadis still; bubbling along at 85". The Northern Echo. Retrieved 19 September 2008.

- ^ Days, pp 169–170.

- ^ "Season 1949–50". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ Malam 2004, p. 84

- ^ Malam 2004, p. 87

- ^ Malam 2004, p. 88

- ^ a b c d e Days, pp. 183–184.

- ^ a b c Days, pp. 185–186.

- ^ "Portsmouth 0 – 2 Sunderland". Soccerbase. Retrieved 6 January 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Richard Rundle. "Football League 1959–60". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008.

- ^ Days, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Dykes, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Days, pp. 201–202.

- ^ Days, p. 205.

- ^ Days, p. 206.

- ^ Days, p. 215.

- ^ Days, pp. 217–218.

- ^ a b Days, p. 225.

- ^ "Shocks do happen". The FA. Archived from the original on 5 March 2005. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ Days, p. 230.

- ^ "Southampton 1 Manchester United 0". FA Cup Finals. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ a b Henry Winter (7 April 2008). "Ledley volley sends Cardiff City to FA Cup final". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 28 November 2008.

- ^ Bennett, Steve. "End of a North-East legend : News 2009 : Chortle : The UK Comedy Guide". chortle.co.uk.

- ^ a b "European Competitions 1973–74". Rec.Sport.Soccer Statistics Foundation. Retrieved 19 December 2008.

- ^ Days, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Days, pp. 239–240.

- ^ a b c Days, p. 245.

- ^ a b Days, p. 247.

- ^ Days, pp. 247–248.

- ^ Days, pp. 251–252.

- ^ Days, p. 252.

- ^ Days, p. 253.

- ^ Days, p. 257.

- ^ "1985 Milk Cup Final". Sporting Chronicle. Archived from the original on 29 August 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ Richard Rundle. "Football League 1984–85". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 18 April 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ a b Days, p. 263.

- ^ a b Richard Rundle. "Sunderland". Football Club History Database. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ Days, pp. 265–266.

- ^ Richard Rundle. "Football League 1987–88". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Days, pp. 275–276.

- ^ "Newcastle 0 – 2 Sunderland". Soccerbase. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "On this Day – May". Sunderland A.F.C. Retrieved 5 January 2011.

- ^ Rundle, Richard. "Football League 1990–91". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Liverpool 2 – 0 Sunderland". LFC History. Archived from the original on 26 February 2007. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ "Sunderland 2 – 1 Chelsea". Soccerbase. Archived from the original on 18 May 2005. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Days, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Days, pp. 287–288.

- ^ Days, p. 290.

- ^ Days, p. 291.

- ^ a b Days, p. 292.

- ^ Days, pp. 293–294.

- ^ "Sunderland 2 – 1 Man Utd". Soccerbase. Archived from the original on 7 October 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Sunderland 1 – 0 Arsenal". Soccerbase. Archived from the original on 19 May 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Sunderland 3 – 0 Chelsea". Soccerbase. Retrieved 6 January 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Richard Rundle. "FA Premier League 1996–97". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Premier Passions (TV Series 1998– ) – IMDb" – via imdb.com.

- ^ Hunter, James (11 June 2017). "Sunderland's Premier Passions remembered 20 years after fly-on-the-wall TV came to Roker Park". nechronicle.

- ^ a b "Stadium of Light". Sunderland A.F.C. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "I Left My Heart in Roker Park". 11 August 2014.

- ^ "I Left My Heart in Roker Park by Tom Kelly". 13 February 2014.

- ^ "Theatre review: I Left My Heart in Roker Park... (And Extra Time at the Stadium of Light) at Customs House, South Shields".

- ^ "Share your Stadium of Light tales". 11 May 2017.

- ^ "English Premier League: Each Club's Most Famous Fans". Bleacher Report.

- ^ "Peter O'Toole and a lost Sunderland passion | Salut! Sunderland". Archived from the original on 26 March 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

- ^ "Peter O'Toole Dies – Sunderland Most Famous Supporter is Dead". 23 December 2013.

- ^ Duncan Adams. "Sunderland AFC". Football Ground Guide. Archived from the original on 7 January 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Rundle, Richard. "Football League 1997–98". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Charlton 4 Sunderland 4". Charlton Athletic F.C. Archived from the original on 1 December 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2008.

- ^ Richard Rundle. "Football League 1998–99". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Bury 2 – 5 Sunderland". Soccerbase. Retrieved 6 January 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Phillips nets Golden prize". BBC Sport. 29 July 2000. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Hetherington, Peter (18 April 2003). "Stadium of Light casts a dark shadow over Sunderland". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- ^ a b Richard Rundle. "2001–02 FA Premier League". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Rundle, Richard. "FA Premier League 2002–03". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Wilkinson takes Sunderland job". BBC Sport. 10 October 2002. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Tim Rich (11 March 2003). "McCarthy set to take charge as Wilkinson goes". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "McCarthy back to coalface". BBC Sport. 12 March 2003. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Rundle, Richard. "Football League 2003–04". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Sunderland 2–1 C Palace". BBC Sport. 17 May 2005. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Rundle, Richard. "Football League 2004–05". Football Club History Database. Archived from the original on 21 October 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "English Premier League – 2005/06". ESPNsoccernet. Archived from the original on 23 October 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ "Sunderland sack manager McCarthy". BBC Sport. 6 March 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ "Sunderland 2–1 Fulham". BBC Sport. 5 May 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Louise Taylor (6 August 2008). "Keane eyes Mido and Gordon as Ranieri backs Black Cats to surprise". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Sandy Macaskill (30 May 2008). "Premier League new boys face uphill task". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved 18 January 2009.

- ^ Mark Buckingham (8 August 2007). "Black Cats sign Gordon". Sky Sports. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Julian Taylor (26 April 2008). "Sunderland 3–2 Middlesbrough". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ Owen Phillips (25 October 2008). "Sunderland 2–1 Newcastle". BBC Sport. Retrieved 2 November 2008.

- ^ a b "Keane resigns as Sunderland boss". BBC Sport. 4 December 2008. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- ^ "Sbragia appointed Sunderland boss". BBC Sport. 27 December 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- ^ Rob Stewart (27 May 2009). "Steve Bruce set for Sunderland talks while Ellis Short completes takeover". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 27 May 2011.

- ^ "Bruce named as Sunderland manager". BBC Sport. 3 June 2009. Retrieved 26 September 2009.

- ^ "Sunderland AFC's academy graduates – where are they now?". 2 November 2018.

- ^ "Former Liverpool chief explain Jordan Henderson transfer cost him his job". 15 August 2019.

- ^ "Inside story of what happened on night of Liverpool's CL final win". 24 July 2019.

- ^ "Martin O'Neill sacked as Sunderland manager after Manchester United defeat". Sky Sports.

- ^ "Paolo Di Canio appointed Sunderland head coach". BBC Sport. 31 March 2013 – via bbc.co.uk.

- ^ "Di Canio: David Miliband quits Sunderland role". BBC News. 1 April 2013.

- ^ a b "Miners' Di Canio protest 'will only end with Sunderland campaign support'". BBC News. 6 April 2013.

- ^ "Durham Miners' Association: Our Issues With Di Canio at Sunderland Now Resolved". Archived from the original on 25 June 2013. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ^ Taylor, Matthew (2 April 2013). "Sunderland miners demand return of banner after Paolo Di Canio's arrival". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Miners join opposition to Paolo Di Canio's appointment at Sunderland". The Independent. London. 2 April 2013.

- ^ Magowan, Alistair (14 April 2013). "Newcastle 0-3 Sunderland". BBC Sport.

- ^ Rose, Gary (22 September 2013). "Paolo Di Canio: Sunderland reign that lasted only six months". BBC Sport.

- ^ "Gus Poyet: Sunderland name Uruguayan as new head coach". BBC Sport. 8 October 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ "Gus Poyet: Sunderland name Uruguayan as new head coach". BBC Sport. 8 October 2013. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Sanghera, Mandeep (19 October 2013). "Swansea 4-0 Sunderland". BBC Sport. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Luke Reddy. "Sunderland 2-0 West Bromwich Albion". BBC Sport. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ Phil McNulty. "BBC Sport – Man Utd 2-1 Sunderland (1-2 on pens)". BBC Sport. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ "Sunderland supporters vote with their feet after Aston Villa run riot". The Guardian. 14 March 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ "Sunderland part company with Poyet". premierleague.com. 16 March 2015. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ "Jordan Pickford: Everton confirm £25m, rising to £30m, deal with Sunderland". BBC Sport. 15 June 2017.

- ^ Johns, Craig (26 November 2018). "Sunderland AFC Netflix documentary gets a release date and a title too". Evening Chronicle. Retrieved 29 January 2019.

- ^ "'Sunderland 'Til I Die' Season 2 Will Happen Despite Club Members' Disapproval To Documentary Series". Business Times. 25 August 2019. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019.

- ^ "This is when season two of Sunderland 'Til I Die is set to be released". sunderlandecho.com. April 2020.

- ^ Mennear, Richard (29 April 2018). "Who is Stewart Donald? The Eastleigh chairman set to take control of Sunderland". i. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ Stone, Simon (4 May 2018). "Sunderland: Prospective owner Stewart Donald agrees sale of Eastleigh". BBC Sport. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ "Sunderland: Stewart Donald completes takeover from Ellis Short". BBC Sport. 21 May 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- ^ "Jack Ross: Sunderland name St Mirren boss as new manager". BBC Sport. 25 May 2018.

External links

[edit]- Sunderland at the Football Club History Database